Professor Anne B Smith.

June 25, 2014.

Professor Anne B Smith has been involved in research, advocacy, and policy-making on childhood issues in New Zealand for almost 40 years. She has worked as an academic at the University of Otago, first in the Education Department and later as Director of the Children’s Issues Centre.

Professor Smith has been called on for advice by various governments, departments and ministries in her career. She has had personal contacts with ministers, and government officials, and has taught and collaborated on research with many colleagues. She has also participated in a range of advisory groups, working parties and committees. Her career has been devoted to making New Zealand a better place for families and their children, and to advancing children’s well-being, rights in early childhood education, the family, schools, and in social welfare and legal systems.

Professor Smith’s commentary with Michael Gaffney on future directions for early childhood research was published in the NZ Early Childhood Research Journal..

What was your early life was like?

I was born in Wales in 1940 just after the start of the Second World War. My father served overseas in the 8th army, and because of this was absent for the first 4-1/2 years of my life. My parents met at Art School in Cardiff – unusual then for a young woman to go to Art School, but my mother told me one of her aunts had financed it. Their interest in Art has stayed with me all of my life, even though my father never had paid work through his art. My mother, however, later became an illustrator of books for children. During the war, my mother worked in a carbide factory as a draftswoman, and my grandmother looked after me. My mother and I spent the first few years of life staying with my maternal grandparents but often visiting my paternal grandparents (who also lived in Wales). I remember it as a very happy time with plenty of extended family (aunts as well as grandparents around), and lots of time at the beach playing in rock pools and climbing over rocks. (We lived in Porthcawl, a coastal town in South Wales.) My grandfather was a primary school principal and he taught me to read before I went to school, making my early years at school easy for me. I started school in Tredegar (where my paternal grandparents lived) and we were based there for a few years. By now my dad was back from the war, and had a job in nearby Merythr Tydfil, as a surveyor. I gather that after the war it was difficult to find a job and housing so this must be why we were still living with grandparents. In search of better job opportunities in 1948 my father took a job in the Middle East working as a surveyor for an oil company, the Iraq Petroleum Company. So between the ages of 8 and 9, I had another year of father absence and living with grandparents. But after a year my mother and I had the excitement of travelling to join my father in the middle of the Syrian desert. We took off from Southhampton on the Syrian Prince, a small cargo vessel, and I still remember the overwhelming impression of some of the exotic ports we visited, such as Malta and Tripoli (Libya). We met up with my father in the sun-soaked island of Cyprus, an idyllic spot at the time (especially for a family from cold, wet Wales!), long since discovered by myriad British tourists. We flew in a small plane from Cyprus to the desert oil station in Syria, where I lived with my parents for a happy six months. The oil station was a little colony of British people, and I was the oldest of about half a dozen children. I didn’t go to school at that time, and I remember having a great time playing with other children and reading lots of books. There was a swimming pool and the adults organised lots of family picnics and the like, so there was a close community with a lot of shared socializing.

My parents must have decided by now that I had to go to school, so I was sent back to England to boarding school, Welsh Girls’ School in Ashford, Middlesex. I spent the next 4-1/2 years of my life in this school, and saw my parents once a year, staying with my Welsh aunties and grandparents in the short school holidays. What a contrast that was to a life of freedom – playing and reading! Every moment of my day was rigidly scheduled. I still managed to be a prolific reader, reading my way through all of the books on the shelves of the small library. It was an Anglican school, so we had chapel twice a day and three times on Sunday, including a visit to the local church.

During the time I was at boarding school my brother Gareth, and sister Jane were born. My parents were still in the Middle East, now in Tripoli, Lebanon. Both of my siblings were born in Beirut. Fortunately for my mother, she was able to have domestic help with childcare and house work, and that helped alleviate the stress of having two small children in a foreign country.

In 1954 my family emigrated to New Zealand. It was a long voyage on the Orsova to Sydney and from there on another boat to New Zealand. My father had got a job (from one of his contacts during the war) with the Hauraki Catchement Board in Te Aroha. We were given a sharemilker’s cottage 5 miles from the town. We had to get through a paddock of cows to reach our house! My mother’s life changed dramatically for the worse. I was 14, Gareth was 4 and Jane was 2 when we arrived in Te Aroha. My mother must have been miserable, so isolated from friends and family, so lacking in support, and in a fairly basic house with only a copper to wash the clothes in and no mod cons. I had to catch the bus to school – a long journey every day. I only had two and a bit years of schooling at Te Aroha District High School (it became a college in my last year there). It was not a high standard of education. Many of the teachers had been there for a long time and had not kept up with the latest methods! I was very much an outsider with my English/Welsh accent though I managed to be the Dux two years in a row.

It was certainly a fairly unusual childhood, with much moving between relatives, a close and deep bond with my mother (and to a lesser extent my father), lots of chances for exploration and play, an abrupt banishment to boarding school and then a new life in a different country.

Describe your career path and jobs held

When I left school I worked for a year as a lab technician at the Soil Research Station at Rukuhia outside Hamilton (where my parents lived). I had some idea about wanting to be a scientist, but the work at Rukuhia was somewhat boring and routine, so I was soon ready to move on. My grandfather thought that Home Science was a “good occupation for a woman”, one reason I began studying for a Home Science degree – first in Auckland (where I did Zoology and Chemistry), and then in Dunedin.

I loved being a student at the University of Otago but I was not destined to be a home scientist. For one thing, some of the science (particularly Physics and Chemistry) was hard and my country school had not prepared me for it. I enjoyed some subjects especially Design, Art History and best of all Child Development, and I particularly enjoyed extra curricular activities like the Otago University Drama Society and the Debating Society. During my years flatting in Dunedin I made some lifelong friends. When I finished my Home Science degree I went back to Auckland, where I took a job as a Science teacher at Mount Roskill Grammar. It was a difficult job and again I had little preparation for it, as I did not go to Teachers College to train. I did, however, learn a lot through teaching, though the school was an unpleasant place to work in, and there was a regime that involved a lot of corporal punishment (for the boys). Also, I wanted to continue my studies in Education and Psychology so I went to university part-time. I worked incredibly hard, but it kept me sane and I began to get very good marks (much better than I had for pure science subjects). I think teaching, and the fact that I had a younger brother and sister, 10 and 12 years younger than me, respectively), and that I helped my mother a lot with looking after them, sparked my deep interest in children. After that year in Auckland I returned to Dunedin where I finished my BA in Education. I had some inspiring teachers in Education, in particular Richard Barham and Ken Melvin, both of whom encouraged me to go overseas and do further study. I went back to Auckland to try and earn enough money teaching to go overseas, and to spend time with John, who taught primary school there, who later became my lifelong partner. I taught science at Marcellin College as the only female non religious teacher. It was a much more positive teaching experience than Mount Roskill, as the brothers were very supportive and they seemed to really care about the children. I was often only a few pages ahead of the kids (especially in 6th form Chemistry) but I began to get more satisfaction from teaching.

In 1966 John and I left Wellington by boat (the Achille Lauro) for Southhampton, and an 8 year period of overseas work and study began. We both did supply teaching in London, before I left for Edmonton, Alberta in Canada in 1967 to take up a teaching assistantship. This meant that I got paid to teach a course in Educational Psychology to undergraduates while I did full-time study first for a Masters degree and then a Doctorate. I later got a PhD scholarship that meant that I was better off financially than I had been as a secondary school teacher, and was able to afford my first car! In 1968 John and I got married in Edmonton, and our two children were born during that time. We led busy lives as I finished my doctorate in Educational Psychology in 1971, and learned what it was like to be a working mother and deepened my considerable interest in childcare. (John finished his a couple of years later). The University of Alberta was a prosperous university and a great place to study and teach, alongside about 100 other Masters and 50 Ph.D. students. We had a couple of years as academics in Halifax, Nova Scotia at the Atlantic Institute of Education. I had a Canada Council Research Fellowship so this was my first opportunity to do research, and the area I chose to work in was Early Childhood Education, particularly issues related to quality and learning opportunities for young children. The Institute had a wonderful group of about 20 mature students with diverse practical experiences, who became good friends, and contributed to the breadth of my knowledge about educational issues.

We returned to Dunedin in 1974 with two young children, Catherine aged 4 and Juliet aged 2. I took up a position as lecturer in Education at the University of Otago. I had to lecture in Child Development to massive first year classes – at one stage 700. It was a real challenge and quite a contrast to the more intimate type of teaching that I had done in Canada. I never enjoyed having to repeat my lectures four times to those enormous classes, but being an academic did allow me to bring my personal interests and passions together with my professional life. As I was doing research and teaching about child development, I found out about the positive impact of high quality ECE on families’ lives, and became involved in a community project. Setting up the Dunedin Community Childcare Association in the late 70s was an exciting experience. I worked with some amazing people, Pat Hubbard and Claire Keay, who were to be the teachers at the first childcare centre in Forth Street, and community organisers like Ewing Stevens, a local Presbyterian Minister. When we were setting up the project we managed to fill a hall with 250 people who came to hear about our plans. In 1979 a United Women’s Convention grant enabled me to make a film called “We Can’t Afford to be Casual about Childcare” that was part of advocating for better ECE and policies and funding. It was the start of a long battle (still ongoing) to advocate for young children and their families with the public and the government. It was fantastic too to be able to show people what good quality ECE was in our DCCA project.

In 1995, after 21 years as a lecturer and researcher in Education, I won the position of Director of a new project, a research and advocacy centre called the Children’s Issues Centre. This was an interdisciplinary centre that addressed issues affecting the well-being and rights of children, providing outreach education for professionals working with children in different roles, such as social workers, lawyers, teachers and health professionals, and carrying out research that was relevant to their work. We were funded by a community trust, and the university gave financial support by providing accommodation (an old house in Albany Street). We appointed a secretary, Rachael Brinsdon, and project manager, Nicki Taylor – both highly skilled and talented people, with a huge capacity for hard work. The Vice Chancellor, Graham Fogelberg, was keen to see the Centre take a high profile, so we provided a series of seminars, conferences and publications (and ultimately distance courses), and worked hard to bring research funding into the centre. The 12 years I spent as Director of the Centre were enormously hard work, but also very rewarding. I learned about issues for children well beyond my previous research areas (early childhood education and gender issues). For example one of our major research projects looked at children’s perspectives on their parents’ separation and divorce, and our work became known by parents, lawyers, and judges throughout the country, and helped bring about a change in the law. Our work has been important in changing policies relating to children in many areas, such as corporal punishment, support for parenting, combatting bullying, improving quality in ECE, changing family law legislation, and social work practice. The emphasis has always been on listening to children and giving them a voice in decisions that affect their lives, and helping professionals to do this effectively.

What is your current role and responsibilities?

What is your current role and responsibilities?

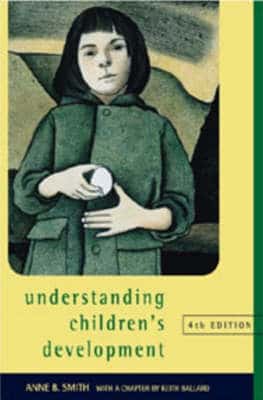

I am now semi-retired and an Emeritus Professor at the University of Otago College of Education. I have worked part-time for the College this year, doing a few lectures to education students, and supporting and supervising postgraduates (including some staff) doing research theses. As well, I continue with my research from home, connecting with the library via my computer, reading, interpreting, analysing, and writing. I am currently working on a 5th edition of my book “Understanding Children’s Development”. In my spare time I visit our daughters, their partners, and grandchildren (five of them) in Melbourne and Invercargill, which widens and deepens my understanding of children. We also love to travel.

Who or what put you on the path to your profession or career choice?

The encouragement of my parents and my lecturers at the University of Otago, combined with an interest in children that started from helping care for my siblings, and was heightened by having children myself, and from my involvement with an important community childcare project.

What is the most interesting aspect about what you do?

Being able to change people’s attitudes and how they treat children. It is a slow process but it does happen. It is now unusual for people to say that it is bad for children to be in early childhood centres, that it is good for children to be smacked, or that children should be seen and not heard. It is also good to be able to get policies changed through basing your arguments on research.

Have you found that there are times when it gets very stressful in your job?

Yes I have been very stressed in my job on many occasions. It was particularly hard when we had to raise funding through research grants, when I was Director of the Children’s Issues Centre. If I was unsuccessful with grant applications it meant that there was no funding for staff salaries. I am very lucky that John is such a supportive partner, because at times I have had to put my job responsibilities before my family responsibilities. He has been very understanding, and supportive in both an emotional and a practical way.

What would you say has been your biggest achievement?

I think that I made a contribution to making New Zealand’s Early Childhood Education system something to be proud of. I have argued strongly for policy changes to improve quality, accessibility and affordability of ECE, and been very critical of governments who have made harmful policy decisions. I also think that I have helped change attitudes towards children, and encouraged a lot of people, both parents and professionals, to recognise children’s strengths, and make sure their rights are implemented. I feel very affirmed by getting an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Oulu in Finland (for my work in early childhood), and being made a Fellow of the Royal Society.

And what would be your biggest regret?

I regret that when I left the Children’s Issues Centre, the Director who followed me did not continue with some of the great projects that we started, and changed the name of the Centre. (The current Director, on the contrary, values the contributions we made, and is likely to continue along a related pathway but in an innovative way.)

For anyone considering a similar career as yours – what two gems of advice might you suggest to them?

If you want to be an academic, it would be a good idea to go overseas and either study or work there. This helps you to understand the issues from a wider perspective.

I also think that it is important to have some practical experience working directly with children, if you are going to be a researcher or tertiary teacher in this area.

Would you ever consider changing careers or your role from your current one?

Not applicable. I wouldn’t have when I was working. The only other possible path for me would probably have been as a public servant working for the government, and I never wanted to do that, as I would not have had the freedom to be ‘a critic and conscience for society’.

Update 22 May 2016

Sadly, Prof Anne Smith passed away on 22 May 2016 at Dunedin Hospital. She is missed as a friend and colleague to many. Her significant contributions to ECE have left a lasting legacy.