This report on staff pay and teacher retention reports on data taken from the 2020 ECE Quality and Employment Survey.

It answers nine questions:

- What do people in the ECE sector earn?

- Are staff paid for all their time spent working?

- Is there regional variation in pay and if so, could there be scope for non-kindergarten ECE staff in any region to be paid more?

- How does staff pay compare between kindergarten and non-kindergarten services? And are pay levels related to staff leaving?

- How does staff pay compare between the main categories of ECE services? And are pay levels related to staff leaving?

- Is the pay of qualified and certificated teachers the same in all centres under the control of kindergarten associations?

- What difference does it make in the pay of qualified and certificated teachers if they work in a kindergarten funded for pay parity compared to another ECE service that is not?

- What proportion of ECE teaching staff have stayed in their job for at least two years?

- Can the ECE sector retain its workforce?

The results are discussed and areas for further investigation of staff pay and workforce retention matters are identified.

In the appendix to this report you can find background information with a short history on setting pay rates in the early childhood education (ECE) sector.

| ATTENTION: EMPLOYERS The Wages and Employee Benefits Guide 2020 – 2021 is available for our ECE Service Provider Members. It gives detailed information on pay benchmarks – see what others are paying their staff and benefits provided. |

Staff Pay and Teacher Retention

The Survey

Wages and a shortage of qualified teachers are major issues facing the early childhood sector. However, there is a lack of available data on the pay of teaching staff across different groups in the sector. There is also a lack of data on teachers’ employment decision-making and intentions. Because of this we know little about whether pay levels are a determining factor in teacher decisions to stay in their job and the interaction between wages and workforce retention.

To learn what the going rates for teaching staff are, we could ask employers. But if we want to know what teachers find they are paid, then we need to ask them. Therefore, at the start of the 2020 school year (late January – February), 4,021 teaching staff in early childhood education (ECE) were surveyed about their work and wages. Of the 4,021 respondents, 4,002 were paid staff and their data is the focus of this report.

A call for participants went out on email to services across NZ. The request may or may not have been passed on by service administrators and employers, so a call for participants was also placed in ECE teacher social media groups. Participants were drawn from across the sector – from diverse centres (e.g. early intervention, Montessori, Rudolf Steiner, bilingual, language immersion centres, teen parent units, etc.), parent-led services, private and community/ public services, and included home-based co-ordinators and visiting teachers.

Participation in the survey was voluntary. There was no obligation to do the survey and no financial or other incentive was offered. To provide assurance on the representativeness of the sample, participants were asked who they worked for. Mega service providers were represented (e.g. BestStart, Evolve, Kindergarten Associations, Provincial, and Kindercare), along with medium-sized through to single service operations. Participation by paid staff from licensed Te Kōhanga Reo was low and therefore their data is reported only as part of all ECE teaching staff and not separately identified.

The survey took place well after the latest re-negotiation of the Kindergarten Teachers, Head Teachers and Senior Teachers’ Collective Employment Agreement (KTCA) resulting in pay increases for kindergarten teachers. The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the increase in the minimum rate for attestation of teacher wages in teacher-led centres will not be known until another survey of teaching staff is done.

However, the Minister of Education said that it was not compulsory that employers spend the 2020 Budget funding increase on the costs of staff on higher than minimum wages. Many early childhood teachers will therefore likely see no increase in wages as a result of the 2020 Budget. Only teacher-led centres that choose to claim a higher funding rate for employing qualified and certificated teachers must now pay all their certificated teachers at least $23.97 an hour. Therefore, centres paying their certificated teachers less than $23.97 will/should now pay their teachers at least $23.97 an hour.

Results

QUESTION 1

WHAT DO PEOPLE IN THE ECE SECTOR EARN?

Answer

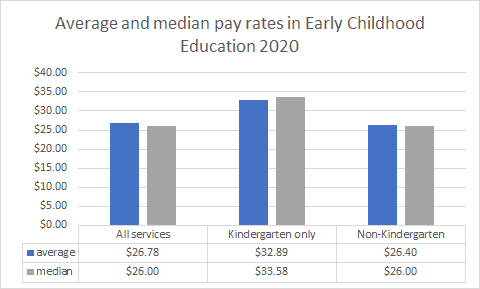

The average pay of ECE teaching staff was $26.78 an hour before tax. Pay rates ranged from $17.00 to $96.00 an hour (median $26.00).

The lowest earning staff reported earning less than the minimum adult wage – for example, an on-call teaching assistant reported pay of $17.48 an hour before tax. (At the time of this survey the minimum adult wage in NZ was $17.70 an hour).

There were teachers in-training on $17.70 an hour. There were qualified and certificated teachers with five or more years of teaching experience earning as little as $18 – $22 an hour before tax. The highest earning staff were mostly in senior positions.

Discussion

Investigation is also needed as to whether teacher-led centres are making correct attestations of teachers’ wages when making their funding claims, and how well attestations are audited by the Ministry of Education.

For the protection of teaching staff against wage exploitation, will the Ministry of Education be concerned to take steps to monitor or will it turn a blind eye to underpayment of teaching staff in publicly-funded services that it licenses? Does there need to be a mandated wage rate that all qualified and certificated teachers, regardless of employer, must at least be paid? These are questions that need to be discussed and considered by policy decision-makers.

QUESTION 2

ARE STAFF PAID FOR ALL THEIR TIME SPENT WORKING?

Answer

Across all ECE services, staff worked an average of four hours a week without pay.

Reports ranged from being paid for all their time spent working to working unpaid for up to an additional 30 hours on average per week (average 4 hours, median 3 hours).

Why is this practice happening? Here are some quotes that help to explain why:

- “A weekly staff meeting is 1h 30m which is not paid, but expected to be attended.”

- “Unpaid for opening and closing centre, 15 mins before or after children arrive/leave each day. I was told that is normal accepted practice.”

- “The number of children I have on my caseload (20) is the number of hours per week that I am paid. New sign-ups in our home-based service generally work out to be extra (unpaid) hours.”

- “I am a manager and I need to shelter the teachers from the ever growing work load. Also, our centre is open from 7:30am to 6pm so the weekends when the children are not there is the only time when the environment can be altered e.g. furniture moved, repaired, etc.”

- “Staying to finish being with an injured or sick child, finishing requirements of my role for the day, catching up on learning stories/planning, talking with parents at pick up time, etc.”

- “Because parents are late picking up children and we have to stay in ratio. We also can’t leave until the room is set up for the next day.”

- “Large documentation expectations and not enough release time due to no cover (lack of staff).”

- “No money to pay for admin staff or extra teachers, so I do extra hours.”

- “Otherwise I will get behind, or jobs not done will have a flow on effect and get more unmanageable.”

- “If we don’t keep up with the work, we will be put on performance review.”

Two problems specific to home-based ECE were being on-call and that work demands occurred outside of normal hours. Here are some examples of what home-based staff said on these matters:

- “I am on call from 6am – 8pm so am obliged to always answer the phone and emails even for the hours that I am not being paid.”

- “Phoning to catch up with families after they have finished work for the day.”

- “Taking phone calls from families and au pairs after work hours.”

In kindergarten services, should a teacher not be needed at work, a benefit of being salaried (as per the KTCA) was as one teacher said: “we even get to go home early sometimes” on pay. However, this was not the case for all kindergarten teachers – it was mainly, but not exclusively, head teachers who worked in excess of salaried hours, in order to complete the work required of them.

In cases where ECE teaching staff were paid for all hours worked, this was largely due to staff ability to say no to working outside of their paid hours, because of employer support, and because of good conditions of work (such as ample non-contact time). Here are a small number of examples of what was said regarding this:

- “As a rule, I don’t. This took me a long time to discipline myself into doing. I feel that as a teacher our passion is held to ransom for us to feel compelled to complete work from home.”

- “I refuse to do extra work at home because our time is not valued. On many occasions the centre has shut early (different reasons) and we are not paid for those hours. My paper work is very behind, but if I can’t get it done in my two hours non-contact then it is not done.”

- “I refuse to do any more than the hours I’m paid for as I am studying and have my own children to look after.”

- “I won’t. I’m worth more than being walked on.”

- “I refuse to work unpaid. My current boss is the first that supports this idea.”

- “In this centre our baby room has 10 infants and four teachers so I don’t need to. At my previous centre with not enough staff I was writing ten learning stories at home because we had no cover for non-contact time.”

Discussion

Four hours a week of unpaid work on average per person, is a significant amount. It seems to be a common expectation in the sector that staff will spend hours of their own time doing work that is essential or required for the service. But it is illegal for an employer not to pay their employees for hours worked when it is necessary for them to work these hours in order to do their job.

When employees are not paid for all hours worked, this brings their effective or real earnings down. In reality, some staff could be earning less than the minimum adult wage and others below the Ministry of Education’s attestation rate when all their hours of work are taken into account. Future pay surveys need to investigate this issue in more depth.

QUESTION 3

IS THERE REGIONAL VARIATION IN PAY AND IF SO, COULD THERE BE SCOPE FOR NON-KINDERGARTEN ECE STAFF IN ANY REGION TO BE PAID MORE?

Answer

Wages for all ECE staff (not including kindergarten) were highest in the Auckland region, followed by the Waikato and Wellington.

The average was $27.47 an hour in Auckland, $27.24 an hour in Waikato, and $27.12 an hour in Wellington. Teaching staff in the Nelson region had the lowest average pay of $25.51 an hour, followed by Northland $25.79 and the Bay of Plenty $26.29.

Discussion

ECE staff in some regions may have more negotiating power over wages than staff in other regions. Perhaps employers in the Auckland region may, for example, be willing to pay more in wages knowing that the cost of living for staff is higher?

Maybe there is scope for services in other regions to be paying their staff more – it could be that services in Auckland, Waikato and Wellington are accepting lower profit. But without recent data on ECE service profitability we cannot know this for sure.

The Ministry of Education should be able to work out roughly what services can afford to pay in wages. The ministry collects copies of the annual audited accounts of services and the accounts provide breakdowns of expenditure and income items. The ministry last did a national survey of service revenue and costs in 2015 because “we need to make sure we have quality information to advise Ministers about the pressures that services face”. In 2018 Dr Sarah Alexander was informed by the ministry that the 2015 results were not available because it was “currently in discussions around the future of data collection in the area, and these discussions will determine our next steps around processing and releasing current data.” (Read about the findings of the Ministry’s earlier cost driver survey here)

QUESTION 4

HOW DOES STAFF PAY COMPARE BETWEEN KINDERGARTEN AND NON-KINDERGARTEN SERVICES? AND ARE PAY LEVELS RELATED TO STAFF LEAVING?

Answer

As shown in the graph below, kindergarten staff were paid an average of $6.49 more an hour than staff in other ECE services (Kindergarten – an average of $32.89 an hour, staff in all other services – an average of $26.40 an hour).

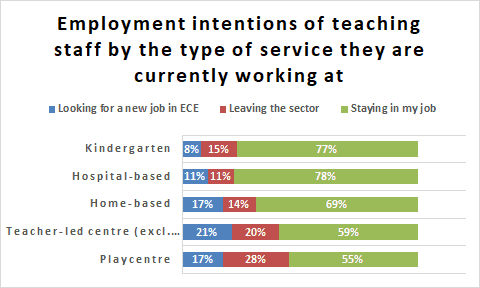

Earning power was found to be related to staff decisions concerning staying or leaving their job and/or the sector. Asked if they were looking to leave their job or if they were staying, 77% of kindergarten staff said they were staying in their job, 15% said they were looking to switch jobs in ECE, and 8% said they were going to exit the ECE sector. But just 60% of staff in other services said they were staying. Nineteen percent said they were looking to switch jobs in ECE, and a much higher percentage compared to kindergarten wanted to exit the early childhood profession and sector (21%).

Discussion

The higher average hourly pay rate of staff in kindergarten compared to other ECE services may, at least in part, be due to government provision of a salary component in the funding of centres under the control of kindergarten associations for kindergarten teacher pay parity with school teachers (for more on this see the information in the Appendix to this report). The government does not provide this additional funding for salaries to ECE services outside of kindergarten associations and neither does it require non-kindergarten services to match the pay of kindergarten and school teachers for their staff. This may put non-kindergarten services at a disadvantage in limiting staff loss because, clearly, higher pay is associated with fewer teaching staff looking to leave.

QUESTION 5

HOW DOES STAFF PAY COMPARE BETWEEN CATEGORIES OF ECE SERVICES? AND, ARE PAY LEVELS RELATED TO STAFF LEAVING?

Answer

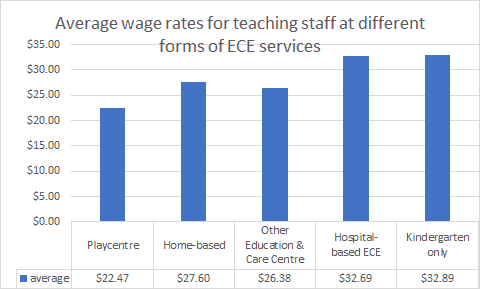

Substantial variation in staff pay was found between different ECE services. The chart below shows that the average wage was $32.89 an hour in kindergarten, $32.69 in hospital-based ECE, $27.60 in home-based ECE, $26.38 in early childcare centres, and $24.47 in playcentre. Kindergarten and hospital-based ECE had the highest average hourly pay rates and playcentre had the lowest.

Note that: teaching staff in hospital-based ECE are paid from District Health Board budgets (with application of the Allied and Public Health Salary Scale to teaching/ hospital play specialist positions). This may help to explain why the pay of hospital-based ECE staff was at a similar level to kindergarten staff and therefore higher than staff in other teacher-led early childcare centres.

A $1.22 difference in the average hourly wage was found between home-based and early childcare centre staff. This probably reflects that most home-based ECE employees had management and co-ordination responsibilities and/ or were visiting teachers whereas the early childcare centre staff also included people who cared for and taught children but were not responsible for supervising other staff or managing programmes.

The graph below shows that staff commitment to their job was strongest in kindergarten and hospital-based ECE – both also being the groups that offered higher levels of pay to their teaching staff (as shown in the graph above).

Of the staff in the kindergarten and hospital-based groups who were looking to leave, pay was not given as a reason. But low pay was a reason for leaving among home-based and other teacher-led early childcare centre staff. (Please refer to Question 10 later in this report for further data and discussion on staff employment intentions).

Discussion

The results show that the category of service people work in makes a significant difference to what they may be paid. Given the differential pay situation, it is unsurprising that home-based and early childcare centre service teaching staff are more likely to want to quit their jobs.

The data here identify a problem for which an effective solution is needed. It seems strange that people can be worse off or better off in pay even though their job of providing early childhood education and care is identical and teaching qualification requirements are identical for all licensed services, bar parent-led services (playcentre employees however may also hold teaching qualifications to Level 7 or higher on the NZQA framework).

QUESTION 6

IS THE PAY OF QUALIFIED AND CERTIFICATED TEACHERS THE SAME IN ALL CENTRES UNDER THE CONTROL OF KINDERGARTEN ASSOCIATIONS?

Answer

In kindergarten the average hourly pay of teachers was $32.89 and this was higher than the average pay of $29.19 an hour of teachers in other centres run by kindergarten associations. An explanation for this difference provided by a teacher was: “I work for an early learning centre operated by a kindergarten association; however, we do not have pay parity with our peers working in the kindy side.”

Discussion

This finding reveals an inequitable situation for teaching staff employed by kindergarten associations. So, what is the Ministry of Education doing to ensure that all qualified and certificated teachers employed in centres under the control of all kindergarten associations are paid on the same salary scale, and on par with teachers in schools? This is a matter that needs to be further investigated.

QUESTION 7

WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES IT MAKE IN THE PAY OF QUALIFIED AND CERTIFICATED TEACHERS IF THEY WORK IN A KINDERGARTEN FUNDED FOR PAY PARITY COMPARED TO ANOTHER ECE SERVICE THAT IS NOT?

Answer

The average hourly pay of qualified and certificated teaching staff working in kindergarten and non-kindergarten services in their first year of teaching was found to be roughly comparable, but differences in pay between the two groups emerged and increased following the first year of teaching.

The average pay of first-year certificated teachers in non-kindergarten ECE was $23.32 an hour (range $18.00 – $33.00, median $23.00). At the time of this survey, a first-year certificated teacher in kindergarten was paid $23.27 an hour or $25.35 an hour depending on qualifications under the KTCA.

The average pay of second-year certificated teachers in non-kindergarten ECE was $23.84 an hour (range $18.00 – $23.39, median $24.00). Under the KTCA at the time of this survey, the pay rate was $24.26 or $26.34 an hour depending on qualification. This means that by the second year of teaching on average the pay of teachers not working in kindergarten was 0.42c or $2.50 less (depending on qualifications) than what they would have been paid had they been working in kindergarten.

By their fifth year of teaching, certificated teachers in non-kindergarten ECE on average earned $25.51 an hour (range $19.00 – $37.00, median $25.48). This was $2.49 or $6.27 less than in kindergarten. (The KTCA salary scale was $28.00 or $31.78 an hour depending on qualifications for a teacher in their fifth year).

In head teacher/ service manager positions teaching staff in non-kindergarten services were paid an average of $32.79 an hour – had they been in kindergarten they would have earned $40.69 an hour (a $7.90 difference)

Discussion

Government policy to fund kindergartens to provide pay parity with school teachers and not include other ECE services, clearly influences what many employers might decide to pay their teaching staff. Certificated teachers not working in kindergarten are financially disadvantaged by this, as evidenced by the growing gap in pay between themselves and kindergarten teachers the longer they stay in ECE.

QUESTION 8

WHAT PROPORTION OF ECE TEACHING STAFF HAVE STAYED IN THEIR JOB FOR AT LEAST TWO YEARS?

Answer

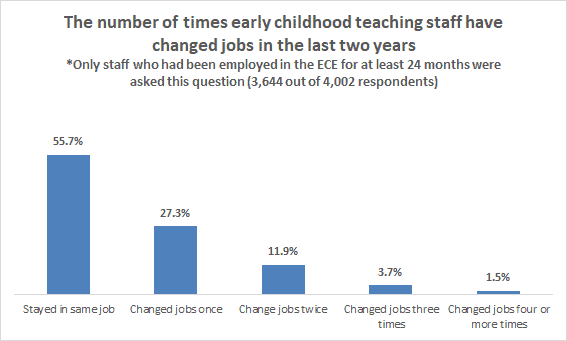

Fifty-six percent of staff who had been in the sector for at least two years had not changed jobs within the last two years, 27% had moved to a new job, and 17% had made two or more job changes.

Job changes were made for career advancement, because they were employed on a temporary contract that ended, for family reasons such as relocating to a new city, for travel and OE and after coming back from this, and because their workplace closed permanently. These are reasons for staff churn that can be expected in any industry or sector.

But there were other reasons too. Around three-quarters of staff who changed jobs within the last two years did so for reasons such as: inflexibility in their terms of appointment, low pay, problems in their workplace, and because of not liking the way they were treated. Here is a small selection of what people said as to what caused them to leave:

- “I had baby and she was not allowed in same centre so I found another centre to work at that would let us be together.”

- “Work were unprepared to allow me to shorten my hours to look after my child.”

- “I left my first centre due to moving out east. Left the second centre due to them changing my hours from regular part-time days to only lunch cover. Now at my third centre and loving it.”

- “Was poached by another centre offering better money and hours. The centre I was at wasn’t willing to change payrate or shift hours to match.”

- “Left my job after one year – pay was terrible and the teacher-child ratios.”

- “High staff turnover over recent years made me felt burnt out and in need of a change.”

- “Service sold and new owner was not nice. I left to seek better pay and for a happier situation – not bullied, and a safer environment for self and children.”

- “Normally moving up the ladder is why I leave, but the last job I left was due to a horrible workplace culture where bullying occurred. As a team leader I voiced my concerns about what was occurring with younger teachers and I became the target. Seven of us finished on the same day.”

- “I left the first time because of the new manager bullying all staff. We all left within 6 months. We were not supported by the governing board regarding this or the manager’s poor teaching standards. The second time I left was because of working conditions. No tea/meal breaks, and over ratio with children in room that I worked in.”

- “I worked in a __ centre – unrealistic ratios/ and illegal ratios. The centre manager changed and had lots of teachers leaving. They struggled to get more, so lunches were not covered properly. No support for teachers – my colleagues were writing reflections and asking for support but the organisation failed to address them. I lasted 3 months. (I have 14yrs experience in childcare). Following job was with a service with two centres. We had a high staff turnover and hired full-time unqualified relievers. The managers were bullying them with what they were doing wrong every day in emails and then set up a meeting to display “disrespect” to teach them their lesson for not being respectful. A mid-forties lovely woman who was our reliever was left with a bruise on her wrist from being pulled around from her chair and had her face smooshed. Management just had no strategies for keeping and working with staff.”

- “Not wanting to be involved in a centre that accepted poor practice and misleads families about the care being provided to their child.”

- “Not being supported by centre manager. Centre manger choosing to overlook staff member who grabbed a child due to not having enough registered teachers. Job being highly stressful. Not best quality care being given due to CM limiting staff and resource budget so she can get her bonus.”

Discussion

A small amount of staff churn can be expected and is a good thing to bring in new people with different skills and recent training into the ECE service. But staff churn is high in the early childhood sector.

The results suggest that better pay, work conditions and support would likely result in fewer staff changing jobs less often. Why is this important? It is important because having a stable staff is linked to child outcomes in the psychological literature on ECE quality. Children who form strong caring reciprocal relationships with their teachers have improved outcomes. But, when staff turnover is high babies, toddlers and young children can struggle to form trusting caring relationships with their teachers. Constantly changing teachers means low quality education for children because it takes time to get to know each child well – their interests, needs, personalities, and learning dispositions.

QUESTION 9

CAN THE ECE SECTOR RETAIN ITS WORKFORCE?

Answer

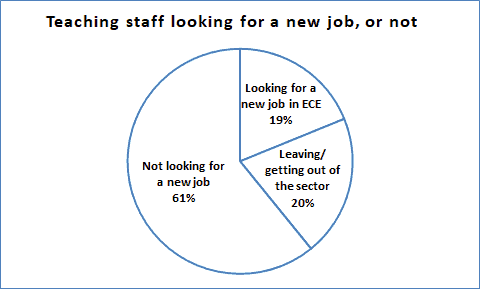

Around four out of every ten early childhood teachers wanted to leave: 19% were looking for a new (better) job in ECE and 20% or one-fifth of teachers were leaving the sector altogether.

In both early childcare centres and home-based ECE the main reasons for exiting the sector were around low pay, hours, stress, and lack of time off. Examples of some of the comments were:

- “Cannot afford to live of the current income and are constantly getting loans just to meet childcare and loving costs.”

- “I cannot afford to stay working in ECE as I am our only income earner for the family so struggle financially.”

- “Now that I’m a mother I have my child to think about. I see no point in paying high registration fees and dealing with the stress of teaching when I can do a basic job for around the same pay and walk away at the end of the shift with no extra responsibilities.”

- “Not enough pay for my hard work. Feeling exhausted at the end of the day and leave cannot be compromised. When I am sick the manager wants to know if I can come the next day even after I said I am away for two days. We rush for things and too much documentation to complete with no extra time allowance to do what must be done.”

- “Leaving the ECE sector as primary teaching offers more release time and pay.”

The main reason for leaving the sector provided by kindergarten staff was bad working conditions, including lack of support from management and work-place stress. Child violence also came up in comments as a reason for deciding to leave, for example one teacher said: “More children with high needs and no practical support such as lower ratio to provide specific care and education. Getting hit by children at work with no safety for me and my staff.” Something that needs to be investigated is whether there is a preference for less experienced teachers by kindergarten associations when making new appointments, and why. A highly experienced teacher working part-time who had tried to get full-time permanent work said that she was now looking to leave the ECE sector because “I have been passed over for the many jobs I’ve applied for. I have heard that teachers over 40 and who are on a higher salary scale are not considered by the association because they are more expensive to employ and speak up more.”

In playcentre, a small minority said they would be leaving soon because it was time to take up other work due to worries about the security of their jobs or to pursue what they wanted to do now that their children were at school or due to start school soon.

In hospital-based ECE the main reasons for exiting the sector were that their role was not valued, they wanted to increase or reduce their hours of work, and that it was simply time to move on – do something different or retire.

Discussion

The data are clear here; staff retention would be helped by making sure that pleasant and safe conditions to work in are provided. Better pay, particularly for early childcare centre and home-based ECE staff would also help in retaining ECE teaching staff. Because early childcare centres and home-based ECE together provide care for around 77% of all children enrolled in ECE, the pay of those who work in these services has a major impact on the ECE sector’s workforce.

One-fifth of teaching staff are looking to exit the ECE sector, therefore workforce retention is a matter that government policy needs to pick up on and address with urgency. If there is no focus on workforce retention in ECE, where are replacements for the teaching staff that leave going to come from? There is already a lack of new teachers coming through training, and training can take three to four years. In September 2019 the Minister of Education allocated $2.176 million for the recruitment of 300 overseas teachers to help to meet teacher supply needs. Randstad was contracted to place 150 of these teachers in NZ early childhood centres by early January 2020. As at June 2020 only 29 overseas teachers had been successfully placed into NZ ECE services.

Discussion and implications

There were teaching staff being paid less than the minimum adult wage. There were trained and certificated teachers being paid less than the minimum wage set by the Ministry of Education for salary attestation. On average every teacher worked an additional 4 hours unpaid per week, just to get the work done that was required of them. Key reasons included understaffing in their service resulting in needing to work when not paid, parents being late to collect their children, other staff needing support, and not getting enough non-contact time to do child assessments, etc. From these findings the following questions arise:

- Should such illegal practices continue to be condoned by the Ministry? If not, then what steps will the ministry take in its role of shaping the direction for early childhood services providers?

- What policies can government put in place to better protect teaching staff in publicly-funded ECE services against exploitation?

The average wage of teachers who work in pay parity funded kindergartens and those who work in another ECE service is roughly the same for their first year of teaching. But after the first year of teaching the difference in pay increases and grows. This finding tells us two things:

- Any increase in the salary attestation rate affecting only those teachers paid the minimum or in their first year of teaching, such as that which was delivered by Budget 2020, would not bring ECE teachers any closer to pay parity.

- Pay parity would be achieved if service providers were required to pay all their qualified and certificated teaching staff as per the KTCA salary scale or the Unified Base Salary Scale for Trained Teachers (which the KTCA is based on).

There are regional differences in teacher pay, with teachers in Auckland, Waikato and Wellington getting more an hour on average than teachers in other regions. There is also a sizeable difference of around $2.00 an hour in wages between private and community owned non-kindergarten ECE services. These results raise a possibility that:

- In some regions service providers may be able to afford to pay their staff more.

- Some privately-owned services may be able to afford to pay their staff more and this needs to be investigated further.

Staff retention is a major issue. Around four out of every ten teaching staff want to leave their job: 19% were looking for a new (better) job in ECE and a further 20% or one-fifth of all teachers were looking to leave the profession. The results show that improving pay would help to improve staff retention in non-kindergarten services and in the sector.

- Pay parity would mean fewer staff will experience the stress of trying to cope when team members leave and when the service is left short-staffed, thereby influencing their choice to stay in their job instead of leave for a job that pays better and is less stressful.

- Pay parity would result in a drop in the proportion of staff looking to leave the profession and would help to retain government investment in the training of these teachers.

Closing Comment on Staff Pay and Workforce Retention

Teaching staff not being paid for all the hours they work, low wages at the minimum adult wage (and even below), and certificated teachers being paid below attestation rates are practices that should not exit in the early childhood sector and need further investigation.

Staff retention would be significantly stronger if it were not for wage inequality. Wage inequality particularly affects people who work in early childcare centres and home-based ECE, and in privately owned early childhood services. Wage inequality would be addressed by ensuring that all qualified and certificated teachers in ECE are paid at levels that match kindergarten (and school teacher) pay.

APPENDIX: INFORMATION ON SETTING PAY RATES

There is no basic salary scale that is applicable across all types of publicly-funded early childhood services for qualified and certificated teachers and/or for untrained teaching staff. In 1985 a joint Departments of Education and Social Welfare paper on the transition of childcare to the education sector noted that to achieve quality childcare adequate working and employment conditions for staff had to be considered. This required “the development of a basic salary scale” for all staff and support for “negotiable conditions of employment”.

A 1987 survey of Christchurch teachers’ wages showed that early childhood teachers were the lowest paid (Department of Labour Statistics Division report). The average ordinary weekly wage per full-time early childhood teacher (including kindergarten, childcare and playcentre) was $261.21 as compared with $445.46 in the primary school system and $464.09 in the secondary school system. That survey was a long time ago and a lot has changed, including teachers in kindergarten gaining pay parity with school teachers.

From 1954 Kindergartens were part of the state sector along with primary and secondary schools. This changed in 1997 when Parliament passed legislation removing kindergarten associations from the State Sector Act, since kindergartens were owned by Free Kindergarten Associations and were not part of the state school sector. In March 2000, as part of the Employment Relations Bill introduced to Parliament, kindergarten teachers were included in the State Sector Act. Under a delegation from the State Services Commissioner the Secretary for Education is involved in negotiating a collective employment. Kindergartens are funded to provide pay parity, as per the collective agreement to all their qualified and certificated teaching staff, including those who are not union members.

In 2002 pay parity for teachers in kindergartens with teachers in primary schools was introduced. The Minister of Education stated that work would be done to extend pay parity to all ECE teachers working in publicly-funded services that were not kindergartens. But, pay parity has yet to be extended to all ECE teachers. Instead, the Ministry of Education asks teacher-led centres when making their funding claims, to attest to paying all their qualified and certificated teachers at least at a prescribed level of pay. The salary attestation rates were $45,491 ($21.87 an hour) for a certificated teacher with a teaching diploma or a 3-year teaching degree, and $46,832 ($22.51 an hour) for a certificated teacher with a bachelor’s degree along with a recognised ECE qualification or holding higher qualifications. The rates were taken from the Early Childhood Education Collective Agreement of Aotearoa New Zealand (ECECA: Dec 2018 – Sept 2019) between NZEI and a small number of early childhood centres. Neither, the Government nor the Ministry of Education play any part in negotiating the ECECA. Kindergartens are not asked to attest that they are paying their staff at KTCA rates – they make the same attestation as all other teacher-led centres.

As part of Budget 2020 the Minister of Education announced that from 1 July 2020 the Ministry of Education would lift the minimum rate for salary attestation to $49,862 (or $23.97 an hour). The new attestation rate was set at the first salary step of the KTCA and the Unified Base Salary Scale for all trained teachers in state and state integrated schools. This came about for several reasons. NZEI had failed to renew its ECECA with employers. Pressure was on the government and the Ministry of Education to increase salary attestation rates. Kindergarten, primary and secondary teachers had already been awarded significant pay rises.

Whether the increase in the attestation rate will make a significant difference to the pay of up to 17,000 ECE teachers as heralded by the Minister of Education and in mainstream media, where “pay parity” was widely but incorrectly reported, will not be known until this Survey is done again. The increase gives pay parity only to those who hold the most basic qualification accepted by the Teaching Council and are beginner teachers in their first year of teaching. Services that do not claim funding for the employment of certificated teachers are not required by the ministry to pay their teachers at the attestation rate and may choose to pay less. The attestation rate does not apply to Home-based ECE (which is a teacher-led ECE service) and to parent-led services even though parent-led services can and do employ teaching staff.

End of Report on Staff Pay and Workforce Retention