An overview of this report

This is the first set of results from the 2023 ECE Quality and Employment Survey of 3,000 teaching staff. The results presented here are on teachers’ perspectives on the quality of early childhood education (ECE), which includes care, for children aged under 6 years in licensed and publicly funded ECE services. The Office of Early Childhood Education’s (OECE) coalface survey has been carried out every three years since 2014.

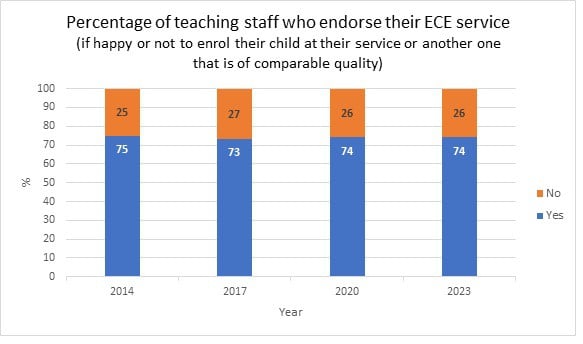

Did respondents endorse the quality of their ECE service? A quarter of the respondents (26%) had so little confidence in the ECE service they worked in that they would not send their own child to it, or to any other one like it.

Did they think children were being effectively educated? More than one-third of the respondents (35%) held concerns for children’s learning. An analysis of their comments revealed less than optimal conditions in services for educating children.

Was there time in their workday to get to know the children in their care well? A third of the respondents (30%) felt they did not have time to develop individual relationships with the children in their care.

Were the regulated ratios for the number of adults to children always met by their service? Of the respondents who worked at teacher-led education and care centres, 45.5% reported that minimum requirements for ratios had been breached at their centre. Five percent of the respondents reported that this occurred all the time, and seven percent often.

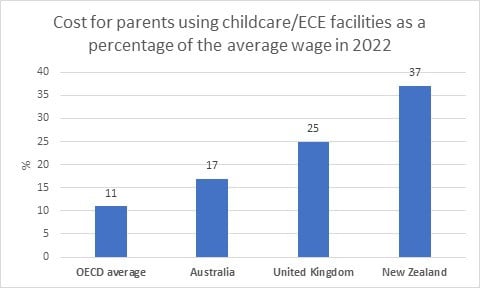

What do the results tell us? The results tell us that while ECE costs for parents in NZ are the most expensive out of all countries in the OECD and per capita funding is amongst the highest in the OECD, our ECE is not necessarily world-class for four reasons:

- The quality of ECE provision for children is variable.

- Children’s well-being is not a high priority in all ECE services as it should be.

- The education system is putting children in ECE at risk of educational failure.

- Nothing has been done that has lifted the quality of ECE provided to children over the past 9-year period of running the teacher survey.

There is a danger of reaching a tipping point when participation in ECE is no longer regarded as a benefit and instead will become a recognised risk factor in the lives of children. It’s not a good sign that the Ministry of Education annual census data shows the number of children attending ECE is declining (in 2017, 202,772 children attended ECE – this has fallen to 181,473 children in 2022).

There is therefore a need for an immediate look at how the sector is controlled and managed and why the Ministry of Education is not getting it right for children.

The ECE system must be about putting children first, their care, their well-being, and their learning, if all services are to be ones that teachers would be happy to enrol their child in.

This report contains an outline of the survey, followed by presentation of the above-mentioned findings. In each results area, possible solutions that emerge from the findings are identified and discussed, and hopefully, taken seriously by stakeholders.

About the survey

A full description of the three-yearly ECE Quality and Employment Survey is available from the website of the Office of Early Childhood Education (OECE).

The survey captures the views of teaching staff in licensed early childhood services across NZ. It is an online survey and voluntary to participate in. The survey asks participants a range of questions concerning their employment, workplace issues, and the standard of care and education provided to children. The 2020 survey received more than 4,000 responses as no limit was placed on responses. For the 2023 survey the survey collector was pre-set to close when the first 3,000 completed responses were received.

This is the first report from the 2023 survey. This report is focused on what respondents said in relation to four questions concerning the quality of provision and children’s care and education.

- Hypothetically if they had a child, would they be happy to enrol their child either at their service or at another service of comparable quality.

- If they had concerns for children’s learning.

- If they felt they had time to get to know each child in their care well and develop individual relationships with children.

- Those who worked in teacher-led education and care centres were asked whether and how often the adult-to-child ratio fell below the minimum legal requirement.

The respondents

The respondents comprised 3,000 staff working in licensed early childhood services from across NZ. Of these, 79% were employed full-time and 13% part-time. Some were casual workers or relief teachers (5%), and a small proportion were on leave or taking a break (3%).

Unsurprisingly, most of the respondents (92% in total) came from teacher-led centres. Smaller numbers of participants came from parent-led centres and home-based ECE. The high proportion of respondents from teacher-led centres reflects that these centres provide the largest source of employment for teaching staff and are also the largest form of ECE provision. Most workers in home-based ECE are independent contractors and not employees – the employees are mostly the visiting teachers and co-ordinators if they are not the service owners.

Many of the participants had been working in the sector for more than 10 years (67%). Most participants were ECE (83%) or primary or secondary (5%) qualified and certificated teachers. Participants came from the private (63%) and community-based parts of the sector (37%).

Are ECEs good enough for the teacher’s own children?

Background information

The Government subsidises the delivery of ECE services for children aged under six years and provides related funds to services. The funding is meant to provide accessible, affordable, quality care and education for children. Per capita, NZ has one of the highest rates of ECE funding in the OECD. Appropriations in Vote Education for the 2023/24 financial year covering ECE total $2.6 billion.

Even with the funding that is paid to services, parent fees or costs are the most expensive in NZ out of all countries in the OECD.

In 2022 the Education Review Office (ERO) analysed its Akanuku Assurance Review Reports and found that 20% of ECE services reviewed were not complying with one or more of the regulatory standards and in 12% of these services non-compliance posed unacceptable risk to children. Note that this is in the context of ERO giving these services four weeks written notice of a review to prepare and present themselves in the best possible light.

The Ministry of Education’s annual report summary on the number of complaints made against ECE services was last published in 2020. The Ministry does not publicly release information on complaints upheld against ECE services for parents to learn about risks.

The number of early childhood services that have their licence downgraded by the Ministry of Education to provisional, suspended, or withdrawn due to serious or multiple breaches in minimum standard requirements has continued to increase over recent years. The data on breaches shows no improving trend in ECE sector adherence to minimum standards.

The Ministry of Education’s latest statistics show that the number of children attending ECE between 2021 and 2022 decreased by 7%, from around 194,000 to 181,000 children.

Survey findings

Respondents were asked a question regarding if hypothetically they had a child, would they be happy to enrol their child at their service or at another one of comparable quality.

One quarter (26%) of the children’s teachers surveyed have so little confidence in the service they work in that they wouldn’t send their own children to it or to any other service like it.

The graph below shows that the proportion of teachers who endorse or do not endorse the quality of their service is similar to what has been reported in earlier surveys of ECE teaching staff. What this tells us is that nothing has been done that has lifted the quality of ECE provided to children as perceived by teaching staff over the past 9-year period of running the teacher survey.

The concerns expressed by respondents in 2023 reflect those expressed in earlier surveys, including concerns about: having too many children to support, not enough teachers, teacher-burnout, teacher quality, low-quality care and educational environments, and the financial management of services.

Here is a sample of comments that cover the main reasons respondents gave as to why they could not endorse their service:

- My child would get lost in the crowd.

- Children are often left to fend for themselves.

- The ratios are horrific, and neglect of children even with passionate teachers who are burnt-out inevitably happens.

- Too many staff changes, lack of quality early childhood trained staff employed, and qualified teachers leaving because they have had enough.

- An unqualified teacher is often outside with children on her own. Sometimes there are more teachers in the office doing paperwork than there are with children.

- Here the teachers are quite often busy doing other jobs instead of being able to sit down and spend time with tamariki. They also don’t have a cleaner which again takes a staff member away from the children.

- Teachers are struggling every day to meet the needs of the children. Four crying babies can take the hands of all teachers, leaving up to 16 other children without engagement. There is no time in our under-twos to provide quality curriculum opportunities (ratios are 1 adult to every 5 under-twos)

- It’s doesn’t matter how caring you are it can never make up for the terrible adult: child ratios and lack of space and resources. Most parents that don’t work in ECE have no idea how bad things really are for their children in ECE.

- Since working in the sector, I have seen far too many issues, and I would prefer not to ever have my children enrolled at any NZ early childhood service.

- I wouldn’t be sending my children to any ECE service anytime soon, especially if I wasn’t there. There is some really yucky practice, and I wouldn’t want my child there without me.

- The fees are expensive, and money is not being invested back into the centre and children to support their well-being.

- The property is not well maintained, and many resources are old and broken. Staff are only paid to start when the children arrive, and the owner arrives even later so the centre isn’t even set up and health and safety checks done before children arrive.

- The manager’s beliefs don’t align with best practice – e.g., that we should toilet train who aren’t ready, so we don’t spend as much money on nappies. Minimal food is provided to children – pasta and rice meals are rotated and called creative names on the menu so parents don’t realise children are given the same meals most days. There’s no option for children to attend part-day and children are forced to attend at least 6.5 hours a day.

A solution for long-term improvement

Currently policy priorities and funding decisions and rules are focussed on upholding the supply of ECE services and supporting the business interests of service operators. Service providers and their paid representatives are on policy advisory groups and lobby effectively for their interests. In this context, adding more funding, changing a regulation on its own such as improving the regulated adult-to-child ratio, or setting up new regulatory and funding reviews would only be addressing problems around the edges within the Government’s current approach to sector management.

But what if children were the priority and the basis for all policy decisions and actions? What if their learning, well-being, and everyday care was the priority? ECE policy and funding could be oriented toward the interests of children. These children are our future, and the actions we take now to improve early childhood education and care can have ripple on effects in the years to come. Rethinking priorities in early childhood policy and funding would be a positive and impactful way forward in recognising this.

Do teachers think that children are being effectively educated?

Background information

Early childhood services are legislated to be places of, and for, education. By law under the Education (Early Childhood Services) Regulations every licensed service provider must: plan, implement, and evaluate a curriculum that is designed to enhance children’s learning and development through the provision of learning experiences and that is consistent with any curriculum framework prescribed by the Minister that applies to the service; and that:

- responds to the learning interests, strengths, and capabilities of enrolled children,

- provides a positive learning environment for those children,

- reflects an understanding of learning and development that is consistent with current research, theory, and practices in early childhood education,

- encourages children to be confident in their own culture and develop an understanding, and respect for, other cultures,

- acknowledges and reflects the unique place of Māori as tangata whenua, and

- respects and acknowledges the aspirations of parents, family, and whānau.

Survey findings

More than one-third of the respondents (35%) held concerns for children’s learning. An analysis of their comments revealed less than optimal conditions in early childhood services for educating children.

The concerns expressed by respondents in the 2023 survey include issues of teachers being stretched beyond the means provided to them, lack of quality teacher to child interactions, meaningful learning is at times non-existent, lack of ECE trained and skilled teachers, too many children for the teachers available, and children coming last over the ECE as a business.

Here is a sample of comments:

- Teacher retention is appalling and there is a constant flow of relievers who can’t plan and support children’s learning.

- Some staff don’t engage or communicate with children at all. The only time they communicate is to tell children to ‘stop crying, you are ok’, ‘it’s lunchtime’, or similar.

- Teachers are stretched beyond capabilities and burnt out, stressed, and tired.

- Due to unmotivated staff who do not provide all the areas of play for children as they do not want to tidy up or put in the effort.

- The children are bored, they have long hours in care, they are needing more quality interactions with teachers, and are not being extended.

- It feels more like a babysitting service where routines like rest and lunch-times are followed only and not an environment where effective learning can take place.

- Two qualified staff, the rest unqualified young ladies who do not understand the importance of face-to-face communication and connection with babies, plus different faces in the room each day…. no relationship. I see children with high emotional needs, a lack of self-regulation, long days in noisy small rooms with unnatural outside areas.

- With 52 children two to four-years in one room we can’t always monitor or plan for the children’s learning adequately.

- There are a lot of tamariki that are falling short with their oral language, emotional and social behaviour and have learning difficulties. We are expected to deal with it daily with a two hour or 1 day course. There are not enough support workers available to support us or the tamariki.

- Management of privately owned education services need to be accountable. We have had access to buying resources restricted, including being able to buy toilet paper and milk for the children.

- The corporate group is not investing in equipment, and the physical environment in our centre is affecting the learning opportunities for children.

- Things are at bare minimum, even the fences. Children can get over the fences and escape.

Solutions / recommendations

The Education (Early Childhood Services) Regulations require that a positive learning environment be provided to children. But if teachers are of poorer quality (e.g., not ECE trained), run down, and spread too thin, how can teachers implement this effectively? They can’t. Moreover, if teachers can’t access the resources they need to support children’s basic care needs, then teachers can’t ensure children are effectively educated. Some solutions include addressing:

- Teacher retention and supply.

Pay parity is key if there is to be improvement in teacher retention and supply and if this improvement is sustained in the long-term. But currently pay parity with teachers who work with older children in schools is assured only for teachers employed by kindergarten associations who work in kindergartens. There is a pay parity scheme for teachers employed in other education and care centres, but this scheme currently relies on employer opt-in, and when teachers get pay increases in schools there is as yet no guarantee from government of a funding increase to centres to increase teacher wages accordingly. - Teacher quality

Target dates need to be set for increasing the proportion of fully qualified ECE teachers working with children (in the adult-to-child ratio) in teacher-led centres to 80% and to 100%.

Additionally, the funding rules and regulations must be changed to recognise and value the early childhood teaching qualification as the benchmark qualification for working in ECE. Teachers qualified to work in school settings with older children but employed in ECE should be asked to upgrade to be ECE qualified, with additional supports available to do so by the Ministry of Education. - Less than optimal environmental conditions for educating children.

An agency is needed to support, advise, and educate service providers and managers to ensure they understand and know how to meet their responsibilities to ensure teachers have resources to meet children’s basic care needs and provide a positive learning environment for children. (Note that the Ministry of Education and the ERO do not have this role). - The support provided to teachers working with children with high needs, including learning difficulties and behavioural challenges.

This could be in the form of paid and funded professional time to support teachers to work with external support agencies to identify learning and behavioural concerns early and be able to implement effective early intervention strategies. It would also be imperative for Initial Teacher Education training institutions to mandate papers for teachers-in-training around how to support children with neurodiverse learning needs. This would better prepare teachers to work alongside allied health professions to support the early identification of support needed for children who may slip through the cracks later in their education, when it then could be too late.

Do teachers have time to get to know children in their care and form relationships with them?

Background information

“Research tells us that children need secure, consistent and responsive relationships with adults” (Early Learning Action Plan Summary, p. 7). The ECE curriculum, Te Whāriki, has an emphasis on relationships that are reciprocal and responsive. Furthermore, it is a legal requirement in the licensing criteria for ECE services that the “adults providing education and care engage in meaningful, positive interactions to enhance children’s learning and nurture reciprocal relationships”.

Survey findings

Respondents2 were asked if they had time to get to know children in their care and develop individual relationships with children.

A third of teaching staff (30%) reported that they did not have time to develop individual relationships with the children in their care.

This result is not statistically different from three years ago in the 2020 survey when 29% of teaching staff indicated they did not have time to get to know children well. Then, three barriers were identified from respondents’ comments: too many children, not enough staff, and additional activities such as cleaning and admin that took them away from their ability to form quality relationships. All three of these barriers were reflected in respondents’ comments in this 2023 survey.

Here is a sample of quotes on the main problems raised by respondents in their comments:

- Too many children and I’m too busy dealing with the chaos.

- I find there are constant interruptions, children butting in, behaving unsafely, (climbing on shelves, throwing things, taking toys from others) and no one else around to help.

- It’s like working in a baby farm or factory. Too busy and teachers hardly have time to do the assessments or provide stimulation for the tamariki. You get the job done and you go home.

- With not having enough staff this means we are just robots, not actually able to spend time with children.

- There are way too many children, too much noise (can’t always hear what the children say), and there’s always something that takes me away from the children e.g., cleaning, dealing with paperwork (on the floor), incidents/accidents, etc.

- The daycare company are more concerned with us keeping to cleaning schedules than teaching and care time for children.

- I have always had great relationships with the children I work with but there simply isn’t the time to stop and build those anymore.

- I feel rushed to just meet routine needs and manage behavioural issues. Quality time with children has declined which I find sad and feel like I’ve failed the children in my care.

Solutions / recommendations

In the licensing criteria for ECE services it is stated that the “adults providing education and care engage in meaningful, positive interactions to enhance children’s learning and nurture reciprocal relationships”. By this definition, one-third of respondents feel their ECE service does not meet this requirement. The issue is teachers feeling rushed, and not having time in their working day that they know they need to have to engage in positive interactions with children and get to know children well. If teachers feel this way, the learning and care that children need to develop well, and deserve, is compromised.

If teachers were better supported with the time needed to form strong relationships with children in their care, children’s wellbeing and quality of their education would increase. This could be achieved if the following actions were taken:

- Group size is regulated separate to licence size.

In 2004, the Ministry of Education noted a need to shift from licence size and group size being treated as one and the same thing, to regulating for small group sizes in centres whatever their licence size. In 2011 the government changed regulations allowing centres to triple their licence size from a maximum of 50 to 150 children (0 – 6 years). However, regulation for small group sizes within the licence was not promulgated at the time, and still has not been promulgated. We know that it is possible for ECE services to implement group sizes separate to licence size. Under Covid-19 rules for operating services at Alert Level 3 services were required to provide care for children in small groups and allocate teachers to each group – which they did. - Teaching staff are supported to focus on educating and caring for children.

The Ministry of Education needs to be providing a strong message and ongoing reminders to service providers, managers, and teaching staff that when in ratio, teachers must be present with the children and involved in activities with them. Teachers should not be asked to, nor permitted to do admin or other tasks when they are with children and counted within the adult-child ratio. - Adult-to-child ratios are tightened.

A decrease in the number of children per teacher in regulated ratios would make a substantial difference – and if teachers are supported to focus on educating and caring for children and services always comply with ratio requirements. (The next section below discusses the need for better enforcement of compliance with adult:child ratios in centres, and the need for ratios to be calculated by group of children or class instead of the current “under-the-roof” approach taken to calculating ratios.)

Are centres meeting ratio requirements?

Background information

By law, all centres that hold full-day licences must have at least 1 adult to every 5 children under two-years. For children two-years and older there must be at least 1 adult for the first 6 children, 2 adults if more than 6 but under 20 children, and one adult for up to every 10 children after that (e.g., 2 adults for 8-20 children, 3 adults for 21 – 30 children, 4 adults to 31 – 40 children, and going up to 15 adults for 141 – 150 children). Centres that hold part-day licences (no child attends for more than 4 hours on any day) must have a ratio of at least 1 adult to every 5 children under two years and 1 adult to every 15 children aged two years and older.

Survey findings

The survey found that 45.5% of the respondents3 who worked in education and care centres including kindergartens reported minimum requirements for ratios being breached at their centre, this included: five percent “all the time”, seven percent “often”, 14 percent “sometimes” and 19.5 percent “rarely”. Only 55.5% respondents from education and care centres reported that ratios were never breached.

Not meeting ratios was a regular and accepted occurrence at some centres for reasons of not being able to afford to employ or find staff to provide cover.

- Often at break times we are out of ratio, for example we had 25 kids today with only two staff while one was on lunch.

- We used to rely on relievers when staff were sick, but it’s extremely difficult now to even have relievers as their pay rates are so high, so we just make do.

Going out of ratio also happened due to staff needs and behaviour.

- Teachers arriving late for their shift or taking too longer breaks leaving the ratios out.

- Multiple teachers going off the floor to vape taking us out of ratio.

- Sometimes teachers become so overwhelmed dealing with children’s terrible behaviour problems that they need to leave the floor to catch their breath.

Centres may rely on children being sick to keep within ratios and then breach ratio requirements when this doesn’t happen:

- The head office moved staff to another centre without replacing them and the relievers just aren’t there to replace them. We rely on children being sick and not coming as the only way of staying within ratio.

- Our centre over-books children, with the hope some will be sick.

Centres may record adults as being on child supervision duty when they are not because they are doing admin, work in the kitchen or laundry, cleaning work, taking a break or taking non-rostered time out from being with children.

- Our centre uses a kitchen person to show we are meeting ratios. Often on paper they put down that she’s with the teachers and children, but she’s not as she’s in the kitchen or other rooms.

- Our manager will put herself down as teaching on paper to comply with ratios but is never in the room with us.

- No admins on site anymore at kindergartens in our association, so teachers are now answering the phones, dealing with walk in inquiries, etc., and this takes us out of ratio.

Solutions / recommendations

Current regulations for adult-to-child ratio set the bare minimum for safe practice as it is. So, the fact that in practice any centre may fall below the minimum requirement, even if it happens only rarely or sometimes, reveals an issue that needs to be addressed through improving enforcement and unannounced visits by the Ministry of Education to see what’s happening in practice, investigating to find out why it is happening, and following up to ensure strategies are put in place to ensure that any breaches do not continue.

As well as more active enforcement of ratios, respondents’ comments suggest a need for regulation to be changed from calculating ratios based on all the staff and children in the centre to calculating ratios per group of children or class within the centre. Here are some examples of the difference between legal ratios and what respondents considered to be safe ratios:

- I have turned up for a shift and there was one teacher with 8 babies on her own, with the other teachers being on the other side of the building in the preschool area. Extremely dangerous conditions for the teacher.

- Across the centre we are ALWAYS legal. But to get work done, often a certain area within the centre is out of ratio, which is dangerous but not illegal, so we put up with it and it keeps happening.

- I work in the over 2s area and there are 2 rooms. During free play the 2 rooms are open so everyone is together but behind closed doors we don’t have the 3 teachers we should have for the room because for the centre the “numbers are fine”.

- I suppose legally we are in ratio but often I am left alone with 20 or more tamariki, and not at a contained time such as mat time but a free play or pack up time. The other teachers are tied up in other areas, such as outdoors, toileting, and changing nappies.

Concluding comments

The survey results suggest that the quality of ECE provision for children is variable, children’s well-being is not a high priority in all ECE services, and the ECE system is putting children at risk of educational failure. Since the survey was first carried out in 2014 and up to the 2023 survey (a 9-year period) nothing has been done to effectively lift the quality of ECE provided to children as perceived by teachers.

Therefore, there needs to be an immediate look at government’s control and management of the sector. The ECE system should be about putting children first, their learning, their care, and their well-being.

Addressing factors impacting on children’s learning, teacher time to get to know the children in their care, and adult-to-child ratios would lift the well-being of children and result in all ECE services being viewed by teachers as places they would be happy for their child to attend. Children benefit from high-quality environments, and this includes small group sizes and having teachers with appropriate training who are well-paid and valued, and have time to form caring, responsive and reciprocal relationships with them.

As mentioned in the introduction to this report there is a danger of reaching a tipping point when participation in ECE is no longer regarded as a benefit and instead will become a recognised risk factor in the lives of children. The ramifications of this risk extend well beyond the years spent in early childhood education.

Our ECE teachers, who have such an important role to play in the development and learning of young children, are calling out for help while doing their best to support children in their most formative years. If we do not prioritise the time for teachers to form strong, responsive relationships, to effectively educate children, and ensure that centres operate at least at or above current adult:child ratio requirements and never below, then we are failing children, and therefore, failing to provide the necessary wellbeing of our future contributors to Aotearoa/New Zealand.

A second report from the survey will be available soon that will give findings on teacher needs and issues impacting on their well-being, employment, and work in ECE services.

Footnotes

- Calculations are for families with two children aged 2 and 3. Parents are aged 40. Net childcare costs are equal to gross childcare costs (fees charged to parents after any public subsidies received by the provider) less childcare benefits, plus any resulting impact in taxes and other benefits following the use of childcare. ↩︎

- Responses were included from 2,726 staff whose role was primarily hands-on with children and not respondents who were staff managers or professional leaders. ↩︎

- This result was drawn from 2,718 respondents from education and care centres only (excluding for example, home-based and Playcentre) who answered the question on ratios. ↩︎