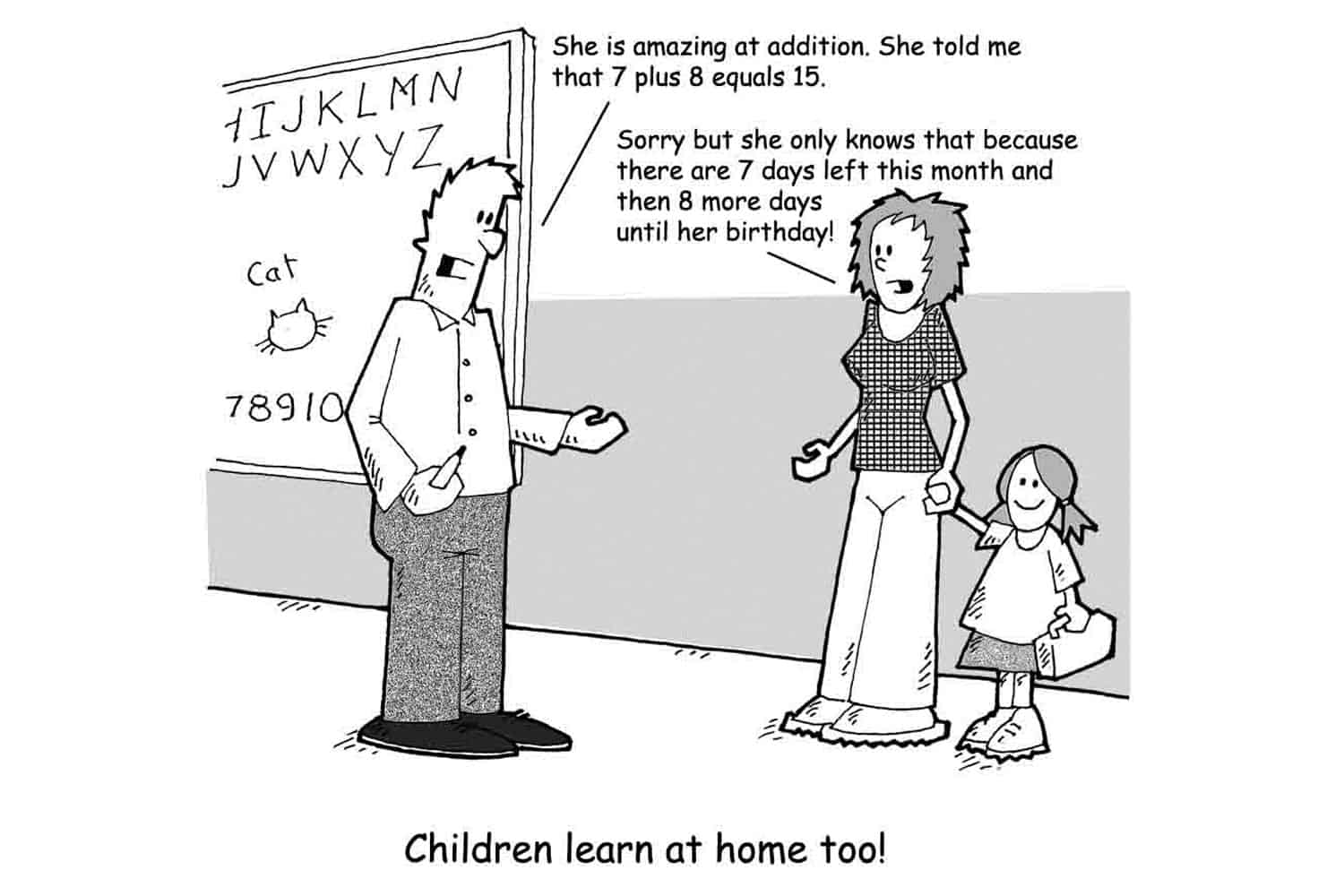

Parents are not amateurs – they play a vital role in children’s early education. They are the central figures in the lives of their children, as they are the heart of their children’s universe.

Unlike the job of childcare done by professional teachers, the job of parenting has little recognition, no status, no salary, no holidays and scheduled tea and lunch breaks, and no incentives for training and professional development.

A child’s learning and relationships with parents and family influences what he/she gains from participation in formal early childhood education. Parents have knowledge of their child that goes across contexts and time.

Professional teachers are involved in children’s learning for a comparatively short period of time in the context of the early childhood centre or licensed home-based setting.

Below are notes from the Keynote Address by Sarah Alexander, to the International HIPPY Symposium, 22 Sept, 2005, in Auckland.

Parenting is Important for Optimal Child Development and Outcomes

There is a preponderance of evidence, strong and conclusive evidence, about the importance of parenting for children’s development and learning in the early years.

The evidence can be grouped into three broad, and often overlapping, areas:

- The importance of parenting for children’s cognitive and language development, including school readiness and subsequent achievement at school.

- The importance of parenting for children’s social and psychological-emotional development

- The importance of parenting for children’s physical well-being, their health and safety.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study invested considerable effort into studying the family relationships and parenting experienced by the study members (Pryor & Woodward, 1996). The researchers found that when children were aged-3 years the mothers’ attitudes toward their child and the mothers’ behaviour (e.g. lack of significant periods of separation) were predictive of intellectual performance and language when the children were aged five-years. They report also that the way in which children are disciplined before age-five and the extent to which their parents agree or disagree on parenting strategies has a significant impact on children’s behaviour in adolescence.

In short, we can learn from this research that by school-starting age how parents have cared for and related to their children is of major importance for language and cognitive performance, and for reducing antisocial behaviour problems during childhood and delinquency and early police contact in adolescence.

Many years ago British researchers, Tizard and Hughes (1984) illuminated for us the cognitive importance of the parent-child relationship and the social context of the home for teaching and learning. They studied the language of four year-old children from working-class and middle-class families at home and at their early childhood centre.

The home for children from both working-class and middle-class families was found to be a much more cognitively rich context for learning than the early childhood centre. At home children had more shared experiences with their parent and family that they could talk about, they were provided with a broader range of play experiences through participation in real-life activities, and they talked about a greater range of things with their parents than they did with their teachers.

University of Virginia researchers (Pianta, et al., 1997) examined the relation between measures of child-parent and child-teacher relationships in the preschool years, and how children’s relationship with their parents and with teachers contributed to children’s outcomes at school. They followed 55 children from families with incomes below twice the poverty level as they participated in preschool and in the first year of schooling.

A finding of particular note was that the mother-child relationship predicted the child’s early school adjustment. Children’s relationships with their mothers were a more consistent and significant influence on children’s adjustment outcomes than their relationships with their preschool teachers. This seemed to be because of the emotion shared by mothers and children. “Affective sharing and warmth and an age-appropriate balance of control and autonomy in mother-child interaction predicated peer social skills, good work habits, frustration tolerance, lack of behaviour problems and overall competency in children’s adjustment” to school (Pianta, et al., 1997, p. 276).

Californian researchers, Lees and Tinsley (2000) examined how mothers’ beliefs and emotional effect are reflected in their health teaching behaviours, influencing children’s behaviour. Forty children aged between four and seven-years and their mothers from middle-class families participated in the study. The study makes a useful contribution to our knowledge in showing that the effects of parental socialisation of health and safety behaviours in the early years extend into the school years, and even after children have grown up and left home.

Mothers who used direct teaching tactics had children who engaged in healthier behaviour. Mothers’ positive emotions during learning and teaching about health were related to children’s healthy behaviour. Interestingly, the mother-child emotional bond did not predict children’s safe actions, but this is probably because teaching about safety tends to occur when children are about to do something that is not safe and therefore parents’ tend to respond with negative effect.

Parents are not amateurs on their own children

The knowledge and experience a parent or primary caregiver acquires in his/her role and through their relationship with their child is uniquely special. Along with this is emotion and love that sets apart the child-parent from the child-professional teacher relationship.

If, tomorrow, you visited the zoo or took a stroll in the park and saw a woman around 30 years-old with a couple of children, how would you know, if she was a parent or a teacher?

It can be hard to know without directly asking. The behaviours professional teachers are likely to exhibit may also be exhibited by parents in such settings.

After observing for some time you may notice a number of things, which, when put together may suggest that the adult is more likely to be a parent than a teacher.

You may see and hear expressions of affection and inclusion. A parent’s love is unconditional. In contrast, as explained by education consultant Anne Meade (1985) children who are quiet, withdrawn, prickly or unlikeable can be left on the fringes of social interaction by their early childhood teachers.

You may observe inter-subjectivity and mutual understandings between the children and adult.

You may hear the adult and children talking about a shared memory or past event, relating this, or various parts of their previously shared experiences, to their current activity.

You may witness interchangeability in the social roles of being teacher and learner as the children and adult engage in the experience, help each other and share their knowledge, thoughts, and questions.

What you may not observe is the breadth and depth of knowledge that their parent has. For example, a professional teacher can make an assumption about what a child knows, thinks, or can or can’t do but this may be mistaken, off beam or incomplete in the light of the further insight and knowledge that a parent brings to understanding their child (Alexander, 2003). The knowledge a teacher has of a child is context-specific, whereas the knowledge a parent has is not bound by the context or setting.

A French study shows that parents, even from very disadvantaged backgrounds, can have a powerful positive effect on children’s cognitive development (Tijus et al., 1997). In the study it was found that the presence of parents participating in an early childhood centre programme alongside the professional teachers helped to create an environment that was richer in cognitive interactions. The parents’ involvement compensated for and mediated the effects of social (ethnic and/or economic) disadvantage on the complexity of cognitive interactions.

The researchers filmed children, parents and professional teachers over a six-month period at four multicultural childcare centres catering for vulnerable or at-risk families. They observed parents participating in their children’s activities and getting the children to participate in more complex cognitive interactions.

The researchers reported that parents were a kind of “naïve tutor, combining some of the positive aspects of an expert with the advantages of a novice”. Parents were closer to the children’s activities and were more truly ‘involved’ in the activity having more joint references with children because they were parents. The parents gained a sense of responsibility as teachers. They came to see themselves as ‘teachers’. They thought about teaching and learning and thus developed their teaching capacity.

What Matters Most is What Parents do for their Children and Not Who They Are

University of Chicago researchers (Christian et al., 1998) when looking at what predicated children’s academic skills on entry to kindergarten at around age-five discovered that regardless of parents’ educational or financial circumstances, seemingly simple behaviours such as monitoring television viewing or taking children to the library substantially influenced children’s growth in academic skills. Children of mothers with less education but a high score for the family literacy environment actually outperformed children whose mothers were better-educated but who engaged in fewer literacy-promoting activities with them.

In a study of the effects of preschool education on over 3,000 children in Britain the importance of home learning was identified (Sylva et al, 2003). In homes where parents actively engaged in activities with children this promoted children’s intellectual and social development. The quality of the home learning environment was found to be more strongly related to child outcomes than SES and parents’ level of education. And the home learning environment was only moderately associated with SES. In other words, how financially rich families were and how well educated parents were mattered a lot less than what parents did to nurture their child’s learning.

Here in New Zealand Megan Goodridge as part of her Ph.D. investigated how Maori, Pakeha, and Samoan families and children construct writing expertise before starting school (Goodridge, 1994). She discovered that even within families of the same ethnicity-culture and social class there were diversity in parental ideas and socialisation practices for supporting children’s emergent literacy.

For example, there was a large difference in the cumulative mean number of writing productions of children in two Maori families. The family of the high literacy producing child provided her with organised learning through tutorial interactions and shared activities at home and in the community. From her kohanga reo the child took home examples of her writing to share with her family. The family believed their child was an active learner but needed to be taught. They guided their child through active participation in literacy activities in many settings and they were responsive to their child’s personal interests in doing this.

In contrast the family of another child gave little support for their child’s early writing. Writing was not a regular activity in the family and was mainly done when the older sibling brought home-work home. The family did not know if the child did any writing or pictures at the kindergarten he attended. The family expressed few goals for writing and held ambivalent beliefs about the need to provide any support. The child produced amongst the lowest number of writing products representing a small range of activities compared with other children in the study. Had this child been attending the same kohanga reo as the first child, the child may well have produced more writing products.

What the family does to support the child’s learning is the critical aspect. This is not only shaped by the beliefs and knowledge of the child’s parents and other family members such as grandparents but also by their confidence and competence to put into practice what they know to help their child.

Programmes to Support Parents as their Child’s Educator are Vital

Programmes that recognise, affirm and strengthen the parents’ role are vitally important because:

- Parents are the central figures in their children’s lives;

- Parenting and parent/family-child relationships have a significant impact on children’s outcomes;

- Not all parents have the skills and knowledge or the personal support to be in the driver’s seat for their child’s learning, and

- Children from a younger age are spending more time in non-family care. While work-life balance is an issue for adults, for many children parent-contact and family time is an issue. Opportunities for parents and children to bond, to learn from each and to build memories are diminishing through the demands of modern living, paid work, television and other time-consumers, and a policy focus on increasing the quantum number of hours children are in the care of professional teachers before starting school.

Research on the factors connected to the change process for families using a Barnardos Family Support Service reports that “most parents had a passionate desire to be better parents and so would willingly participate in any forum which had parenting as a focus” (Sanders et al., 1999, p. 41) .

To nurture (care, protect and educate) a child, parents must themselves feel a strong sense of self-worth and confidence, and be in a position emotionally to be available to parent. They also need the skills and knowledge to put themselves into the drivers’ seat to effectively help their children. This is where programmes such as HIPPY, PAFT, and Family Start that have parent education and learning as an objective, fit in.

Reading the research literature on a range of parent education and support programmes a number of benefits spring up. Programmes may be beneficial for the knowledge parents gain through participation, the skills they learn and develop, and the support they are given in helping to deal with issues and problems. Perhaps the greatest benefit for children comes from the commitment of time that parents must make when they participate in a programme.

In the HIPPY and PAFT programmes, for example, family involvement is essential; parents must be available for home visits and attend group meetings. In the HIPPY programme parents must make time available on a daily basis to engage with their child in a lesson session. The regularity of time set aside for one-on-one interaction, teaching and learning between the tutor or parent educator and the parent, and between the parent and child, over a sustained period of time (two or more years) is important for positive outcomes from participation in these programmes.

For parents, such commitments to involvement in a programme and to teaching their child can only heighten parents’ sense of self-efficacy and give pleasure in the realisation of “I can do it”.

Through their involvement and the support parents receive, parents are more likely to have hope and to look forward. They may see a future beyond the here and now of the difficulties and demands of parenting by being supported, to discover that what they do, can make a positive difference for their child’s outcomes into the school years and beyond.

Conclusion

Social recognition of the role of parents and families in young children’s learning is important. We must give priority to enabling all parents to be in the drivers’ seat to gain a personal sense of efficacy and pleasure for doing well as parents.

Skills, knowledge and support are necessary to parent well. Parents also need the opportunity and time to parent and to have positive relationships with their children.

Why? Because:

- The role of parents and the family in children’s lives is far greater and much more influential than that of their early childhood or school teachers alone.

- There is substantial research evidence that parenting is of critical importance for optimal child development and educational outcomes.

- Parents are not the amateurs in knowing their child.

- What matters most is what parents do for their children, not who they are.

References for Parents are Not Amateurs

Christian, K., Morrison, F.K., Bryant, (1998). Predicting kindergarten academic skills: Interactions among childcare, maternal education, and family literacy environments. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13(3), 501-521.

Alexander, S.E. (2003). Quality teaching early foundations: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Goodridge, M.J. & McNaughton, S. (1994). How families and children construct writing expertise before school: An analysis of activities in Maori, Pakeha, and Samoan families. Reading Forum NZ, 3, 3 – 14.

Lees, N.B. & Tinsley, B.J. (2000). Maternal socialization of children’s preventive health behaviour: The role of maternal affect and teaching strategies. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46(4), 632 – 652

Meade, A. (1985). Are early educators meeting children’s demands or needs? Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 10(1), 46 – 48.

Pianta, R. C., Nimetz, S.L. & Bennett, E. (1997). Mother-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, and school outcomes in preschool and kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 12, 263 – 280.

Pryor, J. & Woodward, L. (1996). Families and parenting. In. P.A. Silva. & W.R. Stanton (Eds.) From child to adult: The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. New Zealand: Oxford University Press.

Sanders, J., Munford, R., Llewelyn Richards-Ward (1999). Working successfully with families: Stage three. Palmerston North: Child and Family Research Centre, Barnardos NZ.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., & Elliot, K. (2003). The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project: Findings from the pre-school period. Unpublished paper, University of London, London.

Tijus, C. A., Santolini, A. & Danis, A. (1997). The impact of parental involvement on the quality of day-care centres. International Journal of Early Years Education, 5(1), 7 – 20.

Tizard, B., & Hughes, M. (1984). Young children learning. London: Fontana.

Key themes

- Parents are not amateurs.

- Good parenting is important for optimal child development.

- What matters most is what parents do for their children (not who the parents are).

- Parents should be supported in being their child’s educator.